Content

IIIH and TAP Blocks

Click on an item to jump to that section.

- Introduction

- Anatomy of the lateral abdominal wall

- Sensory innervation of the anterior abdominal wall

- Concepts of the traditional IIIH and TAP blocks

- Ultrasound-guided IIIH and TAP blocks

- References

Introduction

Pain after cesarean delivery can be a significant burden for a new mother, and can interfere with her ability to care for the newborn. A variety of pharmacologic techniques are at the disposal of the anesthesiologist, including intrathecal opioids, patient-controlled systemic opioid analgesia, and systemic co-analgesics such as acetaminophen and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Regional anesthesia can be incorporated into this practice. The nerves of the lower abdominal wall, where a typical Cesarean section incision is made, can be blocked using two techniques: the ilioinguinal-iliohypogastric nerve (IIIH) block or the transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block.

Anatomy of the lateral abdominal wall

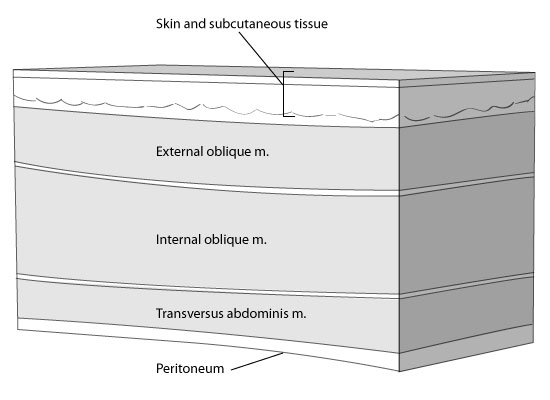

The abdominal wall consists of three muscles layers; from outside to inside, these include the external oblique, internal oblique, and transversus abdominis muscles (Figure 1). Deep to the transversus abdominis muscle is the peritoneum and bowel.

Figure 1. Anatomy of the anterior abdominal wall.

Sensory innervation of the anterior abdominal wall

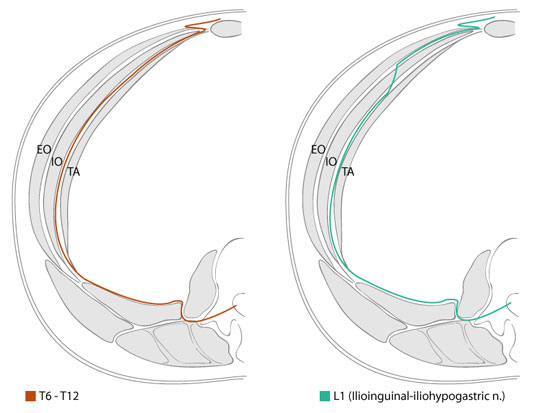

The innervation of the anterior abdominal wall involves the six lower thoracic nerves (T6-T12) and the first lumbar nerve (L1). Upon leaving the intervertebral foramena, the T6-T12 nerve fibres travel between the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles (Figure 2; left). When the nerve fibres reach the anterior border (near the rectus muscle) they pierce the internal and external oblique muscles to reach the surface. The course of the L1 nerve is slightly different. As it leaves its intervertebral foramen, it again travels between the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles (Figure 2; right). At a point approximately two-thirds of the way along this course (near the anterior superior iliac spine, ASIS), it pierces the internal oblique to run between the external oblique and internal oblique muscles. Anteriorly (near the rectus muscle), it pierces through to the surface. The L1 nerve root (which eventually becomes the ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves) is responsible for the sensory innervation of the area of a traditional lower abdominal transverse incision (Pfannenstiel).

Figure 2. Cross sectional view of the abdominal wall. Left: Course of the six lower thoracic nerves. Right: Course of the ilioinguinal-iliohypogastric nerves. EO=External oblique, IO=Internal Oblique, TA=Transversus abdominis.

Concepts of the traditional IIIH and TAP blocks

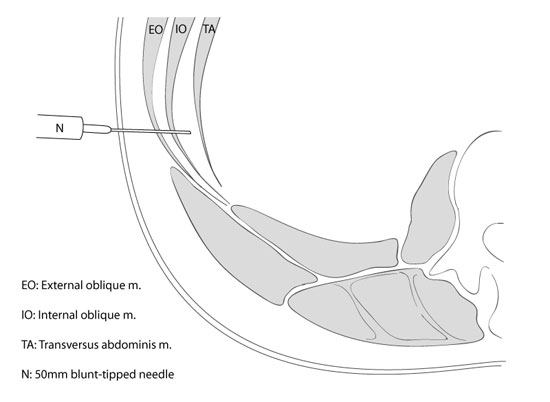

If one deposits local anesthetic in the fascial plane between the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles, then the sensory innervation to the anterior abdominal wall can be blocked. The ilioinguinal-iliohypogastric nerve block is traditionally performed at a location 2cm medial and 2cm cephalad to the ASIS, using a 2-pop technique. The first pop felt by the physician is the needle piercing the fascia between the external and internal oblique muscles, and the second pop is the needle piercing the internal oblique muscle fascia to lie between the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles. The TAP block is also traditionally performed using a 2-pop technique, and local anesthetic is deposited in a similar fascial plane (Figure 3). However, the location of the TAP block is more posterior, in the Triangle of Petit (bordered posteriorly by the latissimus dorsi muscle, anteriorly by the external oblique muscle, and inferiorly by the iliac crest). Being more posterior, the needle is piercing only through fascia, as there is no muscle at this level. Large volumes of local anesthetic in this plane will spread sufficiently to cover a large dermatomal level, compared to the relatively selective action of the IIIH nerve block.

Figure 3. Concept of the TAP block.

Ultrasound-guided IIIH and TAP blocks

By directly visualizing the spread of local anesthetic in the plane between the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles, one can ensure that the deposition of the anesthetic is occurring in the correct plane, which may improve success rates. It is possible to directly visualize the ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves. However, this can be difficult in some patients. The TAP block, on the contrary, relies on visualizing three muscle layers, resulting in a technically easier block to perform. When performed properly, the TAP block should also anesthetize the fibres originating from the L1 nerve root (i.e. the nerve fibres which become the ilioinguinal and ilohypogastric nerves).

The following will describe the technique of the TAP block.

Equipment

- Ultrasound machine with a linear/high frequency probe.

- 20g Quinke-type spinal needle (a short-bevel nerve block needle can be used, but the blunt tip causes significant image distortion).

- Injection tubing to connect the needle to the syringe of local anesthetic.

- 2-20cc syringes of local anesthetic (bupivacaine 0.25% or 0.375% ropivacaine).

- 1-10cc syringe of normal saline

- Sterile prep solution, sterile tray, sterile ultrasound dressing

Operator positioning and location of the block

The operator is positioned on the same side as the block being performed. The block is performed half way between the sites of traditional IIIH and TAP blocks, i.e. just cephalad to the iliac crest. The probe is placed in an anterior-posterior orientation to the patient (Figure 4), and adjusted to obtain the best possible image of the three muscle layers (Figure 5). The needle puncture is performed IN PLANE, medial to the ultrasound probe.

Figure 4. Probe and needle positioning during an ultrasound-guided TAP block.

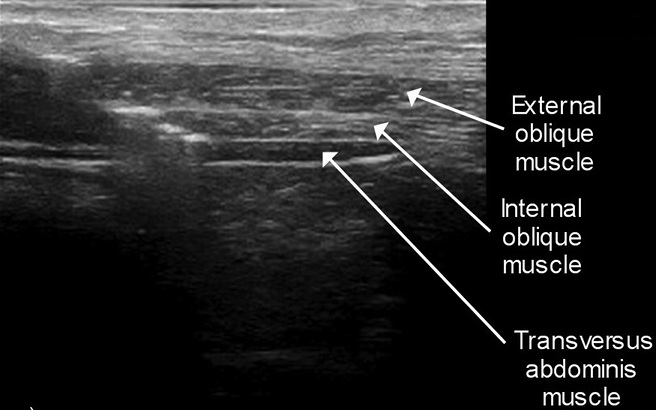

Identification of the muscle layers

Correct probe placement will result in an image of the three muscle layers. The outermost layer is the external oblique muscle. The middle layer, usually the largest and most white layer, is the internal oblique muscle. The last layer is the transversus abdominis muscle, characterized by its very thin and dark appearance.

Performing the block

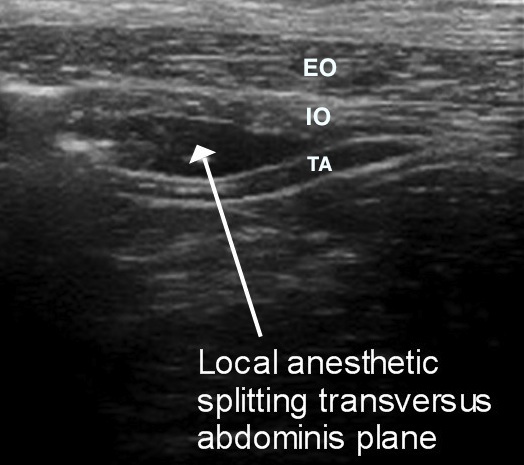

After flushing the needle with normal saline (any air injected will cause serious distortion to the ultrasound image), the operator visualizes the needle IN PLANE as it pierces the external oblique and internal oblique muscles to reach the correct location between the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscle layers (Figure 5). If there is any question as to the needle tip location, 1-2 cc of normal saline can be injected to observe the tissue distortion at the site of the needle tip, a technique called hydrodissection. Once the needle tip is located in the correct plane and saline is injected, the operator will observe the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles separating from each other, forming a black lens-shaped collection of fluid (Figure 6). The normal saline syringe is then removed from the tubing, and 20cc of the local anesthetic solution are injected, resulting in further splaying of the muscle layers. Careful aspiration to identify intravascular placement of the needle must be done after every 5 cc's of local anesthetic injected. The technique is repeated on the other side.

Figure 5. Ultrasound anatomy of the anterior abdominal wall. All three muscles can be easily identified.

Figure 6. Splitting of the transversus abdominis plane during injection of local anesthetic. The internal oblique muscle (IO) and transversus abdominis muscle (TA) separate, forming a black lens-shaped collection of fluid.

Methods to ensure correct needle tip placement

Correct needle placement between the fascial planes results in an obvious splitting of the muscle layers. In addition, the local anesthetic will be extremely easy to inject. Conversely, needle placement in the muscle results in a speckling pattern in the muscle layer, and the local anesthetic will be more difficult to inject.

Complications

The complications reported after traditional IIIH and TAP blocks include bowel perforation, infection, intravascular injection, liver laceration, etc. The incidence of all these complications, however, is extremely low. By using ultrasound guidance to directly visualize needle placement, the incidence of some of these complications, namely bowel perforation and liver laceration, may be minimized.

References

- McDonnell JG, Curley G, Carney J, Benton A, Costello J, Maharaj CH, Laffey JG. The analgesic efficacy of transversus abdominis plane block after cesarean delivery: a randomized controlled trial. Anesth Analg 2008; 106: 186-19.