Patients with heart failure are at risk of arrhythmias, which are abnormal fast rhythms of the heart. When these fast rhythms originate from the bottom heart chambers (the ventricles), they may cause a patient to feel unwell, pass out, or even die suddenly. These abnormal ventricular arrhythmias are called Ventricular Tachycardia (VT) or Ventricular Fibrillation (VF).

What is an ICD?

Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillators (ICDs) are specialized pacemakers. They are able to pace the heart if it beats too slowly, and detect and treat fast rhythms by either pacing the heart or delivering a shock to the heart (defibrillation) to put it back into a normal rhythm.

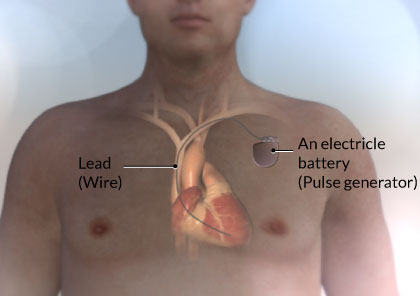

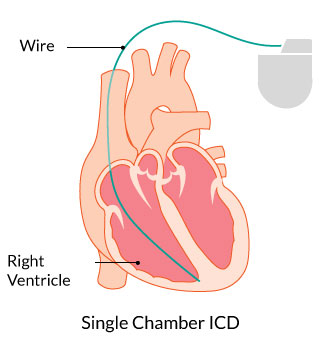

ICDs are composed of a thin metal box that contains a battery, electric circuitry, and a wire that is implanted through a vein and sits in the right ventricle. The wire that sits in the right ventricle continuously monitors the heart rate. If the heart rate drops too low, it will pace the heart. If it detects an abnormally fast heart rate, it will either try to pace the heart back into a normal rhythm or deliver a shock.

When are ICDs required?

Your health care provider will talk to you about whether an ICD is appropriate for you. If you have had a ventricular arrhythmia, felt unwell or passed out, you may be a candidate for an ICD to prevent you from passing out again.

Sometimes ICDs are implanted before a patient develops symptoms related to a ventricular arrhythmia. These are called primary prophylactic ICDs. The decision to implant an ICD depends on how impaired your heart function is (measured by your ejection fraction) as well as how symptomatic you are. Your health care provider will explain to you whether or not an ICD is a good option for you.

Other reasons for implantation of an ICD to prevent against sudden death include genetic cardiomyopathies, such as Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (HCM) and Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy (ARVC).

What are the different types of ICDs?

ICDs vary depending on the number of leads (wires) that are implanted in the heart. The simplest is a Single Chamber ICD, where this is just one wire sitting in the right ventricle.

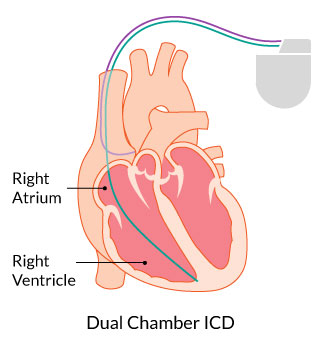

In some cases a second lead may be implanted in the right atrium. These are called Dual Chamber ICDs.

See the next section on CRT to learn more about Biventricular Devices.

How big is an ICD?

The technology continues to improve and the devices continue to get smaller.

Current ICDs are about 2 inches by 2 inches (about 5cm by 5cm) and about half an inch (11mm) thick. They weigh about 1 to 3 ounces (28 to 85 grams).

How are ICDs implanted?

ICD implantation is usually day-surgery. They are typically implanted in the Electrophysiology (EP) Laboratory, but sometimes will be done in the Operating Room. Patients are usually awake during the procedure, and an intravenous (IV) medication is given to help you relax. With this medication, you will feel drowsy, but will be awake and able to answer questions.

Most ICDs are implanted using the transvenous approach. A freezing solution is injected under the collarbone, and a small incision is made. The wire (or wires) are then inserted through the incision into a vein and are then directed to the heart using X-Ray guidance. The tip of the wire is attached to the heart muscle, and the other end is hooked up to the pulse generator. The generator is then implanted under the skin and just under the collarbone. The procedure usually takes between 2 and 4 hours.

After your ICD implantation, you will be given information about your specific device. You will also receive a follow-up appointment in the Device Clinic for ongoing monitoring of your ICD.

What are the risks of an ICD?

In general, ICD implantation is safe, however, as with any invasive procedure, there are risks. The doctor who is going to do the procedure will talk to you more about the risks, and ask you to sign a consent form if you agree to go ahead with the procedure.

In general, the risks of ICD implantation include bleeding, infection, puncture of the lung requiring a chest tube, and damage to the heart or to a blood vessel. Overall, the risk of having any of these complications is about 2 to 3%. The risk of dying from an ICD implantation procedure is very low, and is well under 1%.

In the long term, there is also a risk of having what is called an inappropriate shock. This is when the ICD delivers a shock for the wrong reason (i.e. not for a life threatening arrhythmia). Receiving a shock from an ICD can be painful, and is an unpleasant experience, especially if the shock was for the wrong reason. Again, the technology is improving and the risk of receiving an inappropriate shock is decreasing, but is still around 5 to 6% per year.

What to do if you get a shock?

Receiving a shock from your ICD can be a painful and upsetting experience. If you experience a shock, for your safety and for the safety of others, do not drive. If you are standing, move to a seated position. If you are otherwise feeling well, you do not need to call 911 or go directly to the Emergency Department.

If you experience just one shock, do not pass out, and otherwise feel well, you should call the Device Clinic the same day, or the next business day, to report that you have received a shock. They will likely make an appointment for you to come in to have your ICD interrogated.

You should go to the Emergency Department if:

- you lose consciousness

- experience more than 1 shock in 1 day, or more than 1 shock in 1 minute

- experience chest pain, shortness of breath, lightheadedness